Assistive Technology for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

Inclusive Technology Accommodating Autism Needs

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a developmental disability. It can affect communication, social interaction, and behavior. People with ASD may experience the world differently than others. They may find social interactions challenging, struggle with expressing themselves clearly, and have repetitive behaviors or intense interests. Individuals with ASD can also have exceptional strengths in areas like visual processing, detail-oriented thinking, and creative problem-solving, but not always. For some people with autism, their ASD overlaps with another condition such as depression, ADHD or intellectual disability. The most prevalent comorbidity is ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) at about 50% of all ASD kids, closely followed by anxiety, with research suggesting approximately 40% of autistic children and teens deal with anxiety disorders in addition to ASD. Children with ASD exhibit a higher incidence of sleep disturbances and gastrointestinal issues compared to their neurotypical counterparts, and may be at a higher risk of epilepsy and other seizure disorders. Some autistic people have a higher than average IQ; they do well in school as children and teens, and are successful, independent adults. Others may be considered to be dealing with more extreme behavioral issues. Some parents of children with autism who have intellectual and developmental disabilities that severely affect their lives and cause lengthy hospital stays use the hot-button “profound” autism term, which is rejected by autism advocates and experts, who debate whether a child so labeled might not do much better with different support and accommodations, whether that’s simply a more understanding environment or assistive technology specifically designed for autism users. In any case, it’s not correct to use labels like high or low functioning. As described by autism self-advocates, these labels aren’t helpful, and they can make it more difficult for autistic people to get the right help and make their own best choices.

For many autistic people, their autism is simply part of them, and how they engage with their peers and surroundings. They may even see autistic thought, responses and behaviors as an approach to life that makes more sense than what’s referred to as “neurotypical” conduct and social manners. Certainly people with autism often have a high respect for, reliance on, and enjoyment of, logic, knowledge and facts.

In other wording use: while a large proportion of disability advocates will advise the use of person-first language to describe a person with a disability, such as, “a person with X disorder” or “a person who is blind”, many or even most people in the autistic community do prefer to describe themselves using identity-first. Mariah introduces herself this way: “Hi, I’m Mariah, an autistic person”. Naveed is proud of his autistic identity, and considers it a central part of what makes Naveed, Naveed. He’ll introduce himself like this: “Nice to meet you, I’m Naveed. I’m Autistic.” He feels recognized and appreciated as himself in this way. Positions differ, and different people will, of course, have their own opinions and wishes. The key here is to speak from a position of respect for every individual. Ask, don’t assume.

Autism By The Numbers

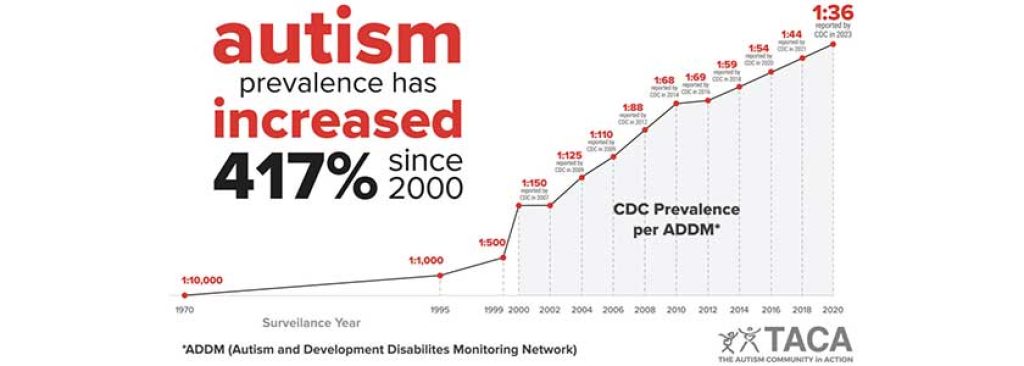

In the United States, CDC research from 2023 estimates that 1 in 36 children is diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder across all racial, ethnic and socioeconomic population sectors, up from 1 in 44 in 2021. That’s 241% higher than 2000 baseline statistics, which could mean a greater incidence or simply higher rates of diagnosis. Criteria for autism diagnosis has also changed drastically from strict 70s standards to more open-ended current diagnostic qualifications. It’s also believed that higher rates of diagnosis may well be linked to an expanded awareness of what autism looks like when it’s not paired with intellectual disability (ID), based on an increase in cases diagnosed, but a smaller percentage of ASD diagnoses co-occurring with ID. 40% of autistic children are nonverbal, and close to 78% experience concurrent mental health problems.

Educational achievements in individuals with ASD show a diverse range: about 33% of young adults with autism attend college, reflecting both challenges and achievements in the education system for individuals with ASD. While high school success for autistic students can translate to college enrollment, navigating its independent environment with new demands can be challenging. Organizational difficulties, compounded by the absence of familiar support structures, can lead to overwhelmed students. Addressing these challenges through preparatory tools and continued access to support and appropriate care is essential for their continued success. Unemployment and underemployment remain serious concerns for autistic adults, at 75% overall and 85% of those with a college degree. However, employment is not the only marker of life success, and with 78.8% of school-age students with autism doing well in a minimum of 1 in 5 major developmental areas by age 10, parents and students have much to hope for.

Boys (or AMAB) are 400% more likely than girls (or AFAB) to be diagnosed with autism, a difference that remains biologically unaccounted for. Among adults, recent studies suggest that around 2.21% of the U.S. population is on the autism spectrum, indicating a broader recognition and diagnosis of ASD in all age groups.

Globally, autism affects approximately 1% of the population, with prevalence rates varying by region. Two areas with a higher-than-average rate of autism prevalence: California, at 1 in every 26, with Florida close behind as a US state, and South Korea at 1 in 38. Qatar reportedly has high rates of diagnosed autism, which may be linked to consanguineous marriage or again, to good healthcare leading to better options for diagnosis. France is said to have fairly low rates, and Texas is the US state with the lowest reported diagnostic prevalence. Do France and Texas actually have fewer people with autism, or are doctors there less predisposed to call it? We may never know.

What Is Neurodiversity?

ASD is one of the cognitive differences that falls under the modern category of neurodiversity. This is a fairly new concept and term that is commonly used, but only partly acknowledged by the more entrenched authorities. Neurodiversity isn’t in the DSM, for example: the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. The DSM is a reference manual for and by health care professionals, considered by most to be the authoritative diagnostic guide for mental and cognitive disorders, in the US and worldwide.

Neurodiversity is a term that first appeared in 1998 as part of the fight for acceptance and inclusion of people with autism, and the removal of the stigma associated with autism. Judy Singer, who is also on the autism spectrum, is an Australian sociologist. She came up with the word “neurodiversity” as part of a thesis on the emergence of a “disability and social movement”. The term corresponds with “biodiversity”, which also works for Singer as a conceptual analogy. “Why not propose,” she argued, “that just as biodiversity is essential to ecosystem stability, so neurodiversity may be essential for cultural stability?” More than terminology, the word “neurodiversity” was intended to be an activation point for a social justice movement advocating for “neurological minorities”. Singer’s ideas were later written into her book, “Neurodiversity: The Birth of an Idea” © 2016 and 2017 Judy Singer.

Within the category of neurodiversity there are multiple cognitive disorders, including autism, ADHD, dyslexia, dyscalculia, and others. An even more recent theory, Complementary Cognition, by Dr. Helen Taylor, PhD, a Research Associate and Project Lead on the Complementary Cognition, Entrepreneurship & Societal Adaptation at the University of Strathclyde, builds on Singer’s work and proposes that societies are entirely too quick to dismiss differences as problems, and that adapting as a group to work with a variety of behaviors is in our best interest as a species. This theory shifts the focus from “is this brain broken” to “how can we take down barriers that obstruct the inclusion of people with brains that don’t work exactly the way ours do.” Twenty-some-odd years later, Singer has recently walked back some of her earlier idealistic thoughts, introducing another term, NeuroRealism, meaning that she believes the movement has gone too far, and it’s important to meet everyone’s needs in an evidence-based way.

As part of popular culture, neurodiversity is increasingly part of the way people with cognitive differences describe and think of themselves today, especially young adults, teens and kids. The neurodiversity movement works from the principle that there’s no “normal” way to think or do or be, just the ways that people are. Each human brain is absolutely unique, and differences occur naturally as people are born and develop as individuals.

What Is Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)?

Autism can be found in the DSM. It’s not a mental illness, like depression. It is what’s termed a disorder, the function of a brain that is structured differently and operates in ways that aren’t found in the average person. A metaphor commonly used by autism self-advocates is positioning typical brains as PCs, and the autistic brain as an Apple Mac. Neither is “wrong”, both are in working order, but they don’t work the same way.

This doesn’t mean that ASD is not a disability. It is.

Rather, it means that autistic people may struggle with some challenges, and will likely indeed require support in some areas of life, depending on their situations and how their autism manifests. However, we should aim our change-making powers at the frictional area between the brain differences and behaviors, and the expectations and barriers that arise from society’s normative expectations.

Autism self-advocacy is part of the disability rights movement. It is a movement led by autistic people, for the benefit of autistic people. It seeks to remove barriers so that people with disabilities are offered equal and equitable opportunities. And, it strives to explain autism in a way that doesn’t look like the scary and extreme portrayals of autism and autistic behaviors in media, movies and online, because stereotypes and myths around autism are never helpful. They can give people the idea that autism must be fixed or changed. It can’t be changed, and it doesn’t need fixed. Autistic people should be supported, not altered.

Nothing About Us: Understanding Autistic Autonomy

As the saying goes, “nothing about us without us.” Autistic people and the autistic community should be consulted and included in decisions, not have decisions made for them. This slogan came into wider use in disability activism, specifically around autism, in the 90s, and is now a catchphrase for multiple minority advocacy groups. Much like the original American colonist frustration with a lack of taxation representation, the idea conveyed by “nothing about us” is that policies should not be made without the full involvement and participation of members of the affected group.

Autistic people have been and continue to be denied some human rights, including barriers in access to healthcare, education, and participation in communities, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Autistic people are met with discrimination as the rule, not the exception, according to UN rights experts. Many autistic adults feel they have suffered by being put into controversial ABA therapy in their childhood as a form of early intervention, with the best of intentions by their parents and guardians. Applied behavior analysis (ABA) has been argued to be effective in controlling autistic behaviors that are thought to be harmful to children. For autistic self-advocates, ABA is not seen as helpful, but harmful. With the removal of punishments in the updated forms of ABA, it may perhaps not be as traumatic, but ABA certainly is still viewed by the autistic community as a wrong-thinking and even abusive method. ABA views autism as a problem to be solved and even a condition that can and should be eradicated, rather than seeing an autistic person as a human being with cognitive differences who needs support and alternate approaches, not “a cure”. Working from a Capabilities Model, which states that all people should be afforded the freedom and the opportunities to flourish and to develop those abilities, we can welcome complexity, promote equity, and affirm the value of autistic people in their contributions to our communities and societies, while supporting and honoring their needs and requirements in a way that is respectful of their dignity and autonomy.

How Can Assistive Technology Support Autistic Individuals?

Assistive technology (AT) can be a valuable tool for people with ASD. These tools can help autistic children and adults with communication, learning, and routine tasks, encouraging greater independence and more comfortable participation in everyday activities. Because ASD is a spectrum, it encompasses a wide range of characteristics, varying significantly from person to person. This means that needs and the support they require will also span a wide range of possibilities. Although the word “technology” is used here, AT can mean anything from a fidget spinner to a brain-computer interface. AT runs the gamut of options, basic to cutting edge.

Supporting Challenges & Sensitivities

Individuals with ASD may experience the world more intensely due to sensory sensitivities, with difficulty experienced in noisy or bright environments. Autistic children and young adults may also have speech and other developmental delays or impairments, as well as cognitive conditions that can commonly appear in tandem with ASD. These differences can make traditional learning environments and everyday tasks daunting.

Social interactions and verbal and nonverbal communication can be significantly harder for autistic people, who may respond differently than their peers expect, appear unusual in their manner or have repetitive behaviors such as “stimming”, a self-regulatory repetitive behavior that most people do when they’re bored or nervous, like tapping a pen or twirling a strand of hair.

7 Common Stims

- Hair twirling

- Repetitive vocalizing or noise-making

- Throwing objects at random or in patterns

- Collecting and organizing items

- Head banging

- Chewing on clothing or objects

- Running, sometimes in patterns

Stimming isn’t wrong or bad in itself, and there’s often no reason to stop a child or adult from doing it, especially when they’re stressed or tired and it’s bringing them comfort. But, when the stim causes physical hurt (like hair twisted dangerously around a finger, or chewed thumbnails that become infected) or discomfort (like a wet shirt sleeve that has to be worn for several hours), it’s a good idea to offer objects that can replace the items or body parts initially used, or tools to calm and help regulate emotions without self-harm, and without classroom or household disruption.

7 Sensory Processing & Assistive Tech Tools For Autism

Items like noise-canceling headphones and textured objects help manage sensory overload, creating a more comfortable environment. Employ these tools and techniques in situations where sensory stimuli become overwhelming, such as in crowded places or during specific activities.

- Fidget Cubes

These small, handheld cubes have multiple sides with different textures and functions like buttons, joysticks, and sliders. They provide a variety of tactile inputs and quiet engagement. - Fidget Spinners

These allow for quiet, repetitive movement that can help with focus and anxiety. Touted as a “magic” tool for ADHD, they serve as a focal point, and can be helpful for autistic people too. - Chewable Necklace

Made from safe, non-toxic materials like silicon, chewable necklaces are a safe alternative replacing chewed fingers, shirts, or other objects. They come in various shapes and textures. - Stress Ball

Squeezing a stress ball provides deep pressure input. This can be calming and help with focus. - Weighted Lap Pads

Similarly to weighted blankets, weighted lap pads provide deep pressure stimulation, which can be grounding and calming. They can be used while sitting at a desk or on the couch. There are also weighted stuffed animals, which can serve as a comfort item that’s also suitable for children. - Noise-Canceling Headphones

These can be helpful in managing sensory overload by blocking out distracting sounds. They can also be used to listen to relaxing music or white noise, which can calm sensory overload. - Sensory Swing

Sensory swings provide vestibular stimulation, which is movement felt by the inner ear. Swinging back and forth can be very calming, and can produce a sense of security. There are many different types of sensory swings available, including platform swings, hammock swings, and pod swings.

It's important to choose stim and sensory objects or tools that are appropriate for the individual's age and needs. Some people may prefer quiet and subtle stim toys, while others may benefit from more intensive or intriguing mental and physical stimulation options.

ASD Use Cases for Sensory Processing Tools & AT

For sensory overload in a multitude of everyday situations, the above tools, technologies and techniques can be used to manage sensory input in different ways, depending on the individual's needs and the specific scenario. For sensory overload online, accessibility overlays can be used while browsing the internet at home, school, or libraries.

Assistive Technology For Autism: Communication, Learning & Living

Assistive technology for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) offers substantial support, helping to improve communication, learning, and daily functioning. Some examples of assistive technology for autism include keyguards to ease computer keyboard navigation, simplified remotes for TVs and other devices, adaptive computer mice, switches that can help kids use their toys, and audio or talking books for all ages. Speech generating devices for autism involving speech delays, nonverbal autism, or selective mutism, apps to ease social interaction, and educational software that’s well-matched to individual learning styles can transform the lives of people with ASD, helping them build pathways to more fulfilling lives.

- Assistive Communication Aids for ASD: AAC

Many individuals with ASD find verbal communication and interpreting social cues challenging, often leading to interpersonal misunderstandings and feelings of isolation. Some autistic people have trouble verbalizing or expressing themselves in verbal ways.

AAC stands for Augmentative and Alternative Communication. AAC devices are tools that help people who have difficulty speaking or using spoken language effectively to communicate. This can be due to a variety of reasons, including autism, cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, or ALS.

Tools like picture exchange communication systems (PECS) or speech-generating devices (SGDs) can provide alternative ways for people with ASD to express themselves. - Unaided AAC: These are tools that don't require any electronics or technology. They can include things like gestures, facial expressions, picture boards, or sign language. Aided AAC refers to electronic or digital devices that help people communicate, and can include low-tech, mid-tech and high-tech tools, devices and solutions.

- Low Tech AAC: These are simple, often portable devices that may use symbols, pictures, or objects to represent words or concepts. For example, a child might have a communication board with pictures of food items they can point to when they are hungry.

- Mid Tech AAC: These devices are more complex than low-tech options and may have features like voice output or the ability to store more messages. They may use synthesized speech or digitized recordings.

- High Tech AAC: The most advanced AAC devices, these represent real-life uses of high tech assistive technology for autism communication support, and can offer a wide range of features, such as touch screens, text-to-speech capabilities, and environmental controls. They can be customized with vocabulary specific to the user's needs and interests.

- Text-to-speech software converts typed text into spoken language, so children or adults having difficulty with verbal communication can write to express themselves clearly.

- Speech generating devices are more advanced AAC devices that can synthesize speech from chosen words or phrases.

- Text-to-speech software converts typed text into spoken language, so children or adults having difficulty with verbal communication can write to express themselves clearly.

- ASD Use Cases for AAC

For trouble expressing wants and needs, communication aids like PECS or SGDs can be used throughout the day, at home, school, or social settings, to facilitate communication.

AAC devices can be a powerful tool for people with communication challenges. They can help people express their wants and needs, participate in conversations, and build relationships with others.

- Educational Technologies for ASD

Tailored learning apps and software address the unique educational needs of autistic students of all ages, focusing on their individual strengths and challenges. These can include software programs, specialized apps, or interactive whiteboards that offer visual support and alternative learning methods. The conventional classroom setup, with its emphasis on group activities and oral communication, often does not suit the learning styles of those with ASD, who may prefer structured, individualized learning approaches. Technologies for education that focus on the needs of autistic learners can be helpful when properly used.

ASD Use Cases for Educational Technologies

For difficulty with traditional learning methods, educational technology tools can be used in classrooms or at home during homework and learning activities.

Integrate these technologies into daily learning routines, both in educational institutions and at home, to support personalized education paths. - Motor & Mobility Tools in ASD Tech

With approximately 4 in 5 autistic children dealing with motor skill issues such as walking, writing, or balancing and in some cases, limited hand control or seizure episodes, some of the tech that can be useful for these children includes:

- Adaptive eating utensils, with thicker handles, built-up grips, or specially angled designs, can help with self-feeding.

- Large-key keyboards facilitate easier typing for children with fine motor skill challenges.

- Gait belts and harnesses boost safety and mobility for children who are unsteady.

- Wheelchairs and scooters offer independent mobility to children who cannot walk, or who cannot rely on a continuous walking ability.

- ASD Use Cases for Motor & Mobility-Related AT

For physical hardship, discomfort or to improve ease of use, select the mobility tools and technologies that fit in budget and best suit individual needs. Remember to check independent ratings and reviews before you buy a tool, for a better sense of how the tools work, and whether they are good quality and long-lasting. - Web Accessibility for Individuals with ASD

Web accessibility overlays, or widgets, are browser extensions that can customize websites by adjusting fonts, colors, and layouts to create a more sensory-friendly experience. By adapting websites to meet sensory and cognitive needs, web overlays can reduce barriers to accessing digital information. Activate when browsing online to customize websites and electronic interfaces with user-selected adjustment directed at individual sensory preferences.

ASD Use Cases for Website Customization

For sensory overwhelm or discomfort, select user options and settings that can help the site work in ways that are accessible to the user. For example, these tools can sometimes be used to remove or pause animations that can trigger seizures in certain individuals. - Social Skills Development Tools

These apps and programs aim to improve understanding of social cues and practice social interactions in a controlled, stress-free environment. Social skills training apps and virtual reality programs offer a safe, comfortable way for autistic individuals to practice social interaction and emotional recognition. Regular practice sessions can help users gradually build confidence and competence in social settings.

ASD Use Cases for Social Skills Systems & Apps

For challenges with social interaction, use these tools to amplify skills levels understanding and learning during therapy sessions, practicing social scenarios, or role-playing with a therapist or caregiver. - Behavioral and Therapeutic Apps

Designed to support coping mechanisms and therapeutic practices, these tools assist in managing stress, anxiety, and other ASD-related challenges. These apps can offer visual schedules, reward systems, and positive reinforcement techniques to help manage challenging behaviors associated with ASD. Use as part of a daily routine or during moments of increased stress to provide guidance and support.

ASD Use Cases for Behavioral Tools

To help manage challenging behaviors, behavioral and therapeutic apps and games can be used at home or in educational settings to implement and encourage consistent behavior management strategies. - Support for Caregivers and Educators

Resources and apps can provide information, guidance, strategies, data collection tools and community support for those caring for or teaching individuals with ASD. Access for ongoing education, communication strategies, and resource networks to sustainably support professionals and family members, and to help them better meet the needs of those with ASD.

Use Cases for Support Resources

When additional support is required, caregivers and educators can make use of resources and apps throughout the day, as needed, to address specific challenges or situations. - Customization and User-Centered Design

Many AT tools allow for customization to best suit individual needs and preferences. In this way, technology serves the specific needs of the user, acknowledging the spectrum of abilities and preferences within ASD. Engage in customization processes during initial setup or when new needs arise, adjusting features to match individual requirements.

Use Cases for Tool Customization

For difficulty using technology independently, personalization options and settings can be explored with the help of a therapist, caregiver, or tech specialist to make sure the technology is user-friendly and meets the individual's specific needs.

These technologies collectively address critical areas of need for individuals with ASD, from improving communication to easing daily challenges. Their effective use can significantly contribute to the autonomy, education, and well-being of those on the autism spectrum.

As science and technology continue to evolve, so too do the possibilities for supporting individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Assistive technology offers a valuable toolkit for encouraging and supporting greater personal autonomy, cultivating communication, and extending alternative learning pathways. By focusing on providing equal access to information, education, and social interaction, these technologies affirm the value and potential of every individual. Recognizing autism as a difference rather than a deficit allows us to appreciate the diverse perspectives and abilities individuals with ASD and other cognitive variations bring to our communities. This collective move towards implementing accessibility not only benefits those with ASD, it enriches human society as a whole, moving us closer to a world where everyone has the opportunity to participate fully, and contribute their unique talents and perspectives in a meaningful way.

FAQs

Absolutely. AT can be a valuable resource for adults with ASD in areas like workplace communication, managing daily routines, finding a calming and centering practice, or staying organized.

Assistive technology designed for learners with autism can dramatically improve their engagement and comprehension, leading to better academic outcomes and feelings of competence and success. These technologies offer customizable learning experiences that can align with each learner’s unique needs and preferences.

Many regions offer grants, subsidies, or insurance coverage for assistive technology for individuals with disabilities, including ASD. It's advisable to research local programs and organizations that provide financial support for such technologies.

Sensory processing technologies, like noise-canceling headphones or tinted glasses, help individuals with ASD manage sensory overload in public spaces, making environments like shopping centers or public transport more accessible.

Caregivers and educators can stay informed by joining ASD advocacy groups, attending workshops and conferences, and subscribing to journals and newsletters focused on autism and assistive technology developments. These resources often highlight innovative tools and best practices for supporting individuals with ASD.